Canadians at Belsen – RCAF 437 Squadron

“Every picture has a story to tell” may be a cliché but it’s an apt description of the story that’s been revealed since I posted one of my father’s favourite Second World War photos on Facebook last fall. The photo, dated April 1945, shows seven young men — my father, Arnold Black, is standing far right — in their Royal Canadian Air Force uniforms posing proudly in front of their airplane.

The photo is more than 75 years old now, but it has opened a window on a war experience my father and his colleagues preferred to keep closed. It’s also a small piece of war history that’s just beginning to be explored by historians.

My Facebook post connected a small group of us, sons and daughters of the young men in the photo, all from RCAF 437 Squadron, and prompted us to dig deeper into our fathers’ papers and photos.

And what we’ve found has left us wondering: why we didn’t ask more questions when our fathers were still alive?

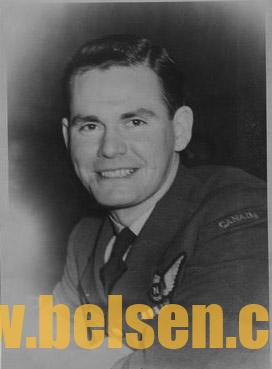

The author’s father, Arnold Black, Navigator with the RCAF 437 Squadron.

We thought we knew their stories, but what we didn’t know is the critical role they played in the evacuation of prisoners from one of Nazi Germany’s most notorious concentration camps, Bergen-Belsen. It’s their story, but it’s also a national story about the critical relief effort carried out by Canadians at Bergen-Belsen, an effort that’s been overlooked for more than 75 years, says Mark Celinscak, professor of Holocaust studies at the University of Nebraska.

April 15 marks the 76th anniversary of the liberation of Bergen-Belsen after it was surrendered to the British by retreating German forces.

What greeted British and Canadian troops when they entered the gates was described by newspapers as a “horror camp” — some 60,000 emaciated people, Jews and other prisoners, all in desperate need of medical attention. It’s estimated that 35,000 people died at Bergen-Belsen, including Anne Frank, who died of typhus just a few months before it was liberated.

Celinscak, author of “Distance from the Belsen Heap,” says that when he started researching Canadian involvement in the liberation of Bergen-Belsen a decade ago, he was told by other historians that he was wasting his time. “‘Canadians weren’t really involved,’ they said. ‘Maybe a guy or two here or there assigned to the British.’” But Celinscak says “that has turned out to be absolutely false.”

More than 1,000 Canadians, Celinscak says, were engaged in the liberation in both an official and unofficial capacity. “Your father and the rest of 437 Squadron were there in an official capacity. To me, that’s why 437 Squadron is really important. They flew not only survivors out of the camp, but high-ranking allied officials into the camp who needed to investigate.”

Joel Zelikovitz of Toronto, whose father, Bill, is one of the airmen in the photo, says, it is “unbelievable” that his father never mentioned Bergen-Belsen. As a Jewish family, Zelikovitz says, “the concept of the Holocaust was central to our upbringing so you would think if he had been to Bergen-Belsen it would be hammered into my head.”

Zelikovitz has spent years putting together a chronology of his father’s war experience. Bill Zelikovitz was a wireless operator who helped drop Canadian paratroopers on D-Day, before joining 437 Squadron in September 1944. Zelikovitz keeps his father’s photos and papers in an old suitcase which he used to take into his kids’ classroom when he visited as a volunteer to talk about Canada’s Second World War history.

William “Bill” Zelikovitz

What tipped us to our fathers’ Bergen-Belsen secret was an email from Jim Vandermeer of Dryden, Ont., whose father-in-law was also in 437 Squadron. Vandermeer had spoken with Pete Porter, another of the airmen in the photo, before he passed away in 2018. Porter had reported that the prisoners from Bergen-Belsen “would kiss the hands of the crew helping them on board” and that while the aircraft “could carry 29 paratroopers, many of the 437 pilots during these mercy missions carried 100 victims.”

Don Sproule of Ottawa, son of Jack Sproule, the 26-year-old commander of Squadron 437, says “it’s almost beyond credibility” that his father never mentioned the evacuation of prisoners from Bergen-Belsen. Sproule decided to see what evidence he could find for himself and went to the website of the National Archives in Britain and downloaded the operation record books of 437 Squadron. There, signed off by his father, was the official document showing the scope of the mission to evacuate and provide supplies to the camp.

The official record reveals the squadron was flying 19 aircraft a day from its base in England to Celle, Germany, the airbase near Bergen-Belsen, sometimes making two trips a day, delivering fuel and removing prisoners.

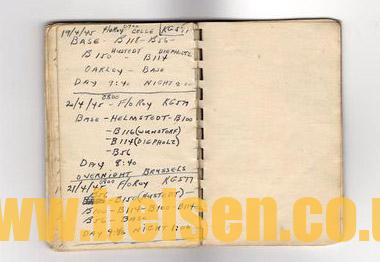

For my father, the war was the highlight of his life. He kept his RCAF uniform in the hall closet and carried the photo I posted in his wallet. He talked a lot about the war so I thought I knew at least the highlights of his story. Then I opened a small notebook he carried with him during the war where he recorded the dates of letters to his mother, his brothers and a girl in his hometown of Timmins, Ont. Turning to the back of the book, I discovered a diary of his daily flights starting April 19, 1945. And there in his own handwriting, are flights to Celle — identified by the British code number B118 — for several weeks in April and May 1945.

A page from Arnold Black’s notebook showing flight April 19, 1945 to B118 British code for airbase near Bergen-Belsen, and returning to B56, the British code for Evere airfield near Brussels.

Looking at the pages from my father’s notebook, Celinscak says “What this shows me is that your father and his colleagues were there really early, just days after liberation. They saw the camp at pretty much the worst.”

Celinscak says that part of our fathers’ silence may have been because the experience of Bergen-Belsen defies language. “No one was prepared for the horror,” he says. “And to try to use language to describe what they saw, there are no words. For them to relate that experience to us, well that’s where language collapses. It’s where meaning collapses.”

Ann Porter of Mississauga says her father, Pete Porter, mentioned the mission to evacuate prisoners from Bergen-Belsen only because she was interviewing him as part of a high school history project. “Otherwise, he never would have talked about it,” she says. Another incident she recalls is “sitting down at the dining room table, and it came upon the news about a guy denying the Holocaust. And then Dad was like, ‘That is not true!’” That was the sort of thing that brought it out into the open.”

While 437 Squadron was part of Canada’s official response to Bergen-Belsen, Canadians from other RCAF squadrons based near the camp took it upon themselves to find ways to help in any way they could. Many of them simply loaded up their military trucks with food and drove to Bergen-Belsen, says Celinscak.

Twenty-three-year-old Ben Delson of Bridgewater, N.S., was one of those Canadians. He was an aircraft mechanic and amateur photographer stationed near Bergen-Belsen. “He went to the camp on his own volition,” says his son, Bob Delson. “He helped feed people and took pictures.” But his black-and-white photos languished in a trunk in the basement of the Delson family home for decades until Bob discovered them in his twenties. When he asked his father about them, “he looked at me and asked, ‘where did you find these?’ He didn’t want to talk about it.”

It wasn’t just airmen who were involved in the relief efforts says Celinscak. There were Canadian doctors, nurses, photographers and war artists.

Aba Bayefsky was a 22-year-old Canadian war artist when he entered Bergen-Belsen in May 1945. In an interview he gave 50 years later Bayefsky said the experience became “the cornerstone of my work.”

Tim Cook, who has written 12 books on Canada’s military history and interviewed thousands of veterans and their children, says our fathers’ silence is a very common story. “It’s very clear to me that there is a great silence over what Canadians had done during the Second World War.”

Cook, a historian with the Canadian War Museum, says the question of why veterans have “felt silenced and why they have been unable to tell their story” are crucial questions and ones that he explores in his most recent book, “The Fight for History.”

“We have a much better sense today of things like post-traumatic stress disorder and the challenges that veterans have in talking about their experiences,” Cook says. “And I think quite clearly, this was a case of the million or so veterans who returned to Canadian society who didn’t have the words to talk about their experiences.”

During the last year of my father’s life I spent many evenings with him talking about his war experiences over a glass of wine. He talked about flying at night using the stars as navigation aids. He showed me a brochure for the Canuck Cave in Brussels where he spent Christmas in 1944. He talked about wearing his RCAF uniform the day he graduated from air school at Toronto’s Malton Airport (now Toronto Pearson International Airport) and dancing the night away at Casa Loma.

These were stories I’d heard many times. I realize now these weren’t the only stories. They were the just the ones he knew the words to.

Karen Black

9,364 total views