Charles Philip Sharp (113th LAA)

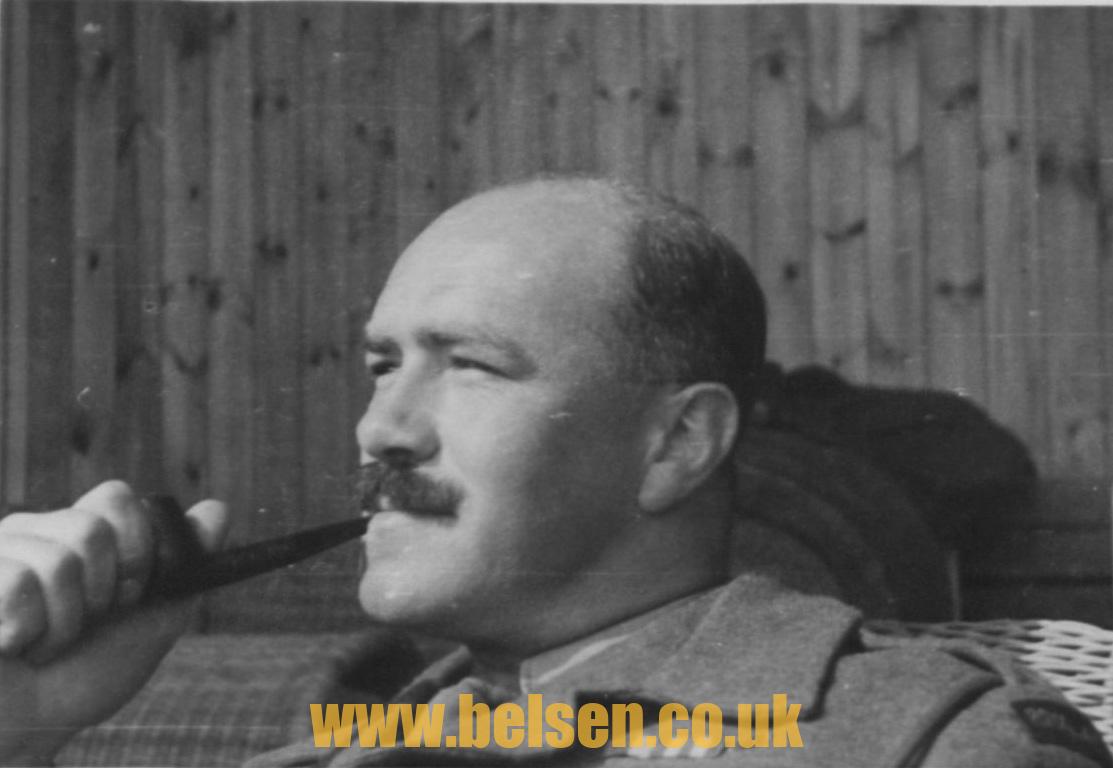

Charles Philip Sharp, known as Philip, was born on April 2, 1912, in Leicester, Leicestershire, England. He had a sister Mignon. Philip had been in the Territorial Army for several years when it was called to duty during the Munich crisis in summer 1938.

Hitler had declared his intention to annex the Sudetenland region of Czechoslovakia. At the Munich Conference in September, the western powers agreed to this action. Philip worked his way up to warrant officer third class and, when commissioned, elected to serve with the 113th Light Anti-Aircraft Regiment, Royal Artillery. He was adjutant to the commander, Lt. Colonel W.H. Mather. Great Britain declared war on Germany on September 3, 1939, following the September 1 invasion of Poland. Philip’s regiment protected the London reservoir and ports in Norfolk and Kent. At 14:30, June 6, 1944, Philip and his unit left on Project Overlord, landing at Juno Beach.

Hitler had declared his intention to annex the Sudetenland region of Czechoslovakia. At the Munich Conference in September, the western powers agreed to this action. Philip worked his way up to warrant officer third class and, when commissioned, elected to serve with the 113th Light Anti-Aircraft Regiment, Royal Artillery. He was adjutant to the commander, Lt. Colonel W.H. Mather. Great Britain declared war on Germany on September 3, 1939, following the September 1 invasion of Poland. Philip’s regiment protected the London reservoir and ports in Norfolk and Kent. At 14:30, June 6, 1944, Philip and his unit left on Project Overlord, landing at Juno Beach.

Six hours (Months more likely! ED) later, his unit crossed the Somme, heading toward Brussels. The troops were besieged by cheering crowds. The unit was attached to VIII Corps and moved ahead to protect bridges over the Rhine River. During Operation Market Garden, the Allied assault of September 17-24, Philip’s regiment was split by a German Panzer division not known to be training in the area. His unit crossed the bridge at Nijmegen, where they held a defensive position for nine weeks, until ordered to Louvain. In late February 1945, Philip received two weeks leave to see his seriously ill father who died during his visit. His mother also had died recently.

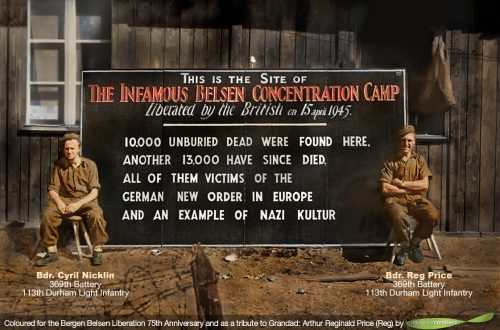

In March 1945, while the unit prepared to cross into Germany, Major Jobbing of 369 company was wounded. Philip was promoted to major and given the command. In early April 1945, Philip received an order to go 250 miles into Germany “to look after a mysterious camp of 50,000.” Philip reached Winsen on April 12, and learned that their destination was Bergen Belsen. The large concentration camp had a typhus epidemic and it was feared that it could spread all over Europe. Conditions were so serious that the Germans negotiated a truce with the British VIII Army. Philip’s unit was selected because they had received double inoculations for typhus. The roads around Celle were filled with thousands of freed slave laborers and POWs. An advance group located the camp on April 15 and, on April 17, Philip was one of the first four British Army officers to enter Bergen Belsen after its liberation.

The guards continued to kill inmates even as British troops entered the camp. When Sharp and his contingent told them to stop, the commandant Kramer asked: “Why? They are Jews.” Kramer was later tried and executed for crimes against humanity. Philip and the three officers headed the post-liberation operation. There were approximately 60,000 prisoners, extremely ill, and many half dead. Their first task was to bury over 10,000 dead inmates. Huts were packed with corpses and there were large heaps of decomposing naked and skeletal bodies all over the camp. Philip was charged with counting the dead, as the Army wanted to know exactly how many they had found. He began with a pile of children; which he estimated at 300. It was often difficult to identify separate bodies, so Philip developed a method of averages based upon the size of a bulldozer load.

Captured German SS were forced to move and carry the dead to the mass graves. The size of the camp and the number and desperation of the prisoners made it difficult to establish order. The conditions of the living inmates were horrendous. The soldiers did their best to care for them. Philip ordered them to shower and then dust the inmates with lice powder to contain disease. Many inmates were already infected with typhus, tuberculosis, and other infectious diseases and they died at the rate of 300 a day. The prisoners’ were starving. They had been without any food for weeks. The soldiers shared their rations, but the inmates could not digest the rich food and many died as a result. There were no sanitation facilities and the camp was chaotic and filthy. Food and supplies were taken from the nearby villages, but more supplies and men were needed. There was an adjacent camp with 12,000 prisoners of war and the surrounding area had to be searched for SS men seeking to escape. After Philip completed the organization of the daily burials, he was assigned to help in the maternity unit. About twenty babies were born in those first five weeks, but few survived. Philip’s final duty at Belsen was to give the order to destroy the camp and burn the barracks.

Philip kept detailed diaries of his five weeks at Belsen about his military duties, and recorded the personal stories of many inmates. Philip left Bergen Belsen on May 24, and was placed on military occupation duty south of Hanover. In addition to his regular military duties, Philip gave public lectures with photos of the concentration camp atrocities. In his journal, he reflected on the routine answer from the Germans he encountered that they could not be responsible for things about which they knew nothing. Philip’s position was that “Atrocity Guilt like War Guilt is not the monopoly of a few. In a less degree the rest of the world is guilty – only the inmates of the concentration camps are innocent.” He noted then, and decades later as he continued to speak about his experiences, that people were unwilling and embarrassed to confront such unpleasant facts, but felt that “It should embarrass and shame all of us that human nature contains such depths of evil.” He believed that people needed to hear about it for “only then can there be any hope of it never being repeated…”

Philip was awarded the Military Cross for bravery. He married Eileen Stevens (1917-1997.) Following the war, he had a notable sporting career as a rugby player and as a president of the Leicestershire Rugby Union. Philip, 86, died on June 11, 1999, in Stoneygate, Leicestershire, England.

11,643 total views