‘Dick’ Everett Jenkins – Medical Student

In April 1945, just before the Second World War ended, nearly 100 medical students from across London volunteered to support the British army. In this group, there were students from St Mary’s Medical School and Westminster Medical School, two of the schools that formed Imperial College School of Medicine. 75 years on, we want to share their stories and celebrate their courage.

The students were told they would be helping the Dutch, who were starving as a result of the Germans cutting off food and fuel shipments. However, the plan changed at the eleventh hour. The group of students were diverted to a recently liberated concentration camp, Bergen-Belsen. Nothing could prepare them for what they would face, but they acted in the best traditions of the medical profession and put their patients first.

To commemorate the 75th anniversary of the students volunteering, we want to recognise our unsung heroes and their life-saving work. We spoke to Dr Chris Everett about his cousin and Westminster student John Richard ‘Dick’ Everett Jenkins. Dr Chris Everett shared Dick’s diary with us. He also explained how Dick nearly died of tuberculosis (TB) and battled typhus. We’ve also shared insightful extracts from the published journal of another Westminster student, Michael John Hargrave.

Bergen-Belsen wasn’t intended to be a concentration camp. It was set up as an exchange camp – the Jewish hostages were going to be used as bargaining chips to free German prisoners held overseas.

But the camp was expanded and people were piled in. In 1943, it was converted into a civilian residence camp, then into a concentration camp. Sanitation was poor and food rations quickly dwindled. Prisoners would often go days without anything to eat.

“So I went and had a look at what I thought was one of the most impressive things about the Camp. It was a pile of shoes, made up of boots taken off of the victims they cremated. I don’t know how many years it had taken the Germans to build up this pile, but it was about 20 yards long by 5 yards across and about 12 feet high – the shoes at the bottom were squashed as flat as paper and so you can imagine how many thousands of shoes there were, and each pair of shoes had an owner…” – Bergen-Belsen 1945, A Medical Student’s Journal by Michael John Hargrave

Saving lives

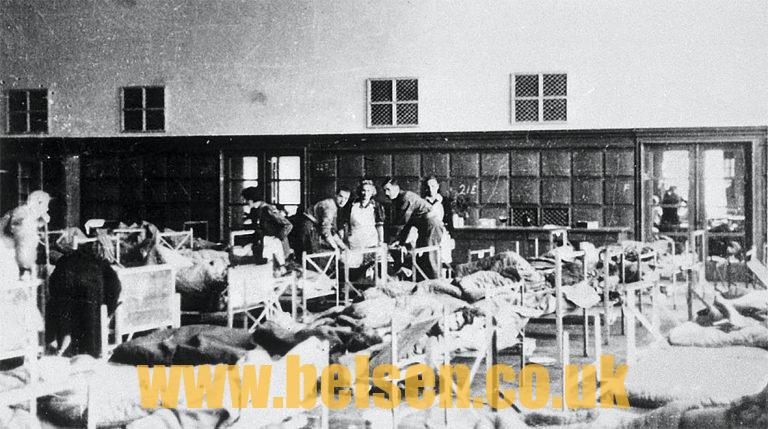

Thousands of unburied bodies. 60,000 starving, mortally ill people. Disease-ridden conditions. When the students arrived at the camp, the horrors they faced are hard for us to imagine today. Despite all of this, they courageously started to put their training into action.

As soon as they could, they cleared the huts and treated dying patients. Many people were suffering from typhus and other deadly diseases. They spent nearly a month carrying out gruelling work until the army hospital stepped in. After returning to London, one author reported that four University College Hospital students tragically died from typhus or TB caught after saving the lives of others at Belsen.

Who were the students?

There were 96 volunteers, including 11 from Westminster Medical School and 11 from St Mary’s Medical School (the schools, along with Charing Cross Hospital Medical School, that form Imperial College School of Medicine as we know it today). Every single day at Belsen tested their medical skills and they sacrificed their personal safety to put patients first.

While many of the students are no longer with us, their legacy lives on. We can still hear about their experiences through stories from relatives and diary entries.

A conversation with Dr Chris Everett

Dr Chris Everett started by telling us, “Dick was 10 years older and like a brother to me. I lived with him and his family in the war because we had nowhere to live. I knew him extremely well. He worked at Westminster Hospital where I subsequently went as a medical student.”

Dick was in his final year of training at Westminster when he volunteered at Belsen. Dr Everett told us, “Dick saw the request for volunteers, along with many others, and put his name on the medical school notice board.” He explained, “They were going to go to Holland. The plan was to help the starving people and get them eating again. It’s very difficult after you’ve been chronically starved. They were all prepared for this – and that’s what they thought they were volunteering for.”

On 15th April 1945, the Germans surrendered Belsen-Bergen camp. While fighting went on around it, the people still alive inside desperately needed help. Dr Everett told us, “Of course, there were no medics available as they were all on the frontline helping the army. So at the last moment, the 96 medical students were diverted to Germany.”

When they arrived, they saw huts grossly overcrowded with starving people and floors piled with human faeces. He said, “The Red Cross had already been there for a few weeks. These ladies were doing their best I’m sure, but apparently they didn’t go into the huts.”

“We fed them all with glucose – biscuits and a cigarette which cheered them up no end.

We have aspirin, opium and sulphadiazole of which we use the sulphur for dressings. One woman had all her extensor tendons on the foot exposed by a sore. They have not been dressed for three weeks – i.e. since Jerry left. Coramine is a drug of addiction in the camp and there is a racket in it somewhere in the camp – something to do with the foreign doctors.

We dressed the worst cases and managed to get the hut cleaned up a trifle and water has now been arranged although what kind of bugs it is just nobody’s business. The smell of rotting faeces & burning pervades everywhere – even here – about 1 mile away.” – Thursday May 3rd

Dr Everett told us, “The medical students went in. They tried to feed them. But, more importantly, they started cleaning the place. There were around 500 people in the huts. Most were very thin and practically dead.”

After the students’ arrival, the death rate started to drop. However, in the time they were there, there were around 13,000 more deaths. The students continued to clean and do everything they could. Dr Everett told us, “The round in the morning consisted of removing dead bodies which was pretty awful.”

The students spent a month at Belsen. Dr Everett explained, “Two days before the students left, the army hospital arrived. After weeks of struggling, you can imagine how frustrated they were to be told how they should be doing things! They were upset – and I think they were all quite glad to get out of there and return home.”

“The ward is really organised and going well now, the nurses are working well, and the patients are beginning to get a certain cheerfulness – good show; apparently, ours is the only ward in the hospital which has got an efficient method of coordination between nurse, orderlies, and stooges and which drugs each one are to give and a decent system further case taking. As a result all the other wards are copying our system.” – Wednesday 23rd May

Returning home

We asked Dr Everett if Dick ever shared his experiences at Belsen. He explained, “Well, funny enough, and it’s common for this era, we never really discussed it. There is a family story though. Dick arrived back in army uniform. He had a girlfriend (who he later married), and so he marched up to the ward where Joan was sitting and said, ‘I’m back’. Joan responded, ‘Where the hell have you been?’ Presumably they’d gone off without anyone knowing.”

Dick nearly died

After returning, Dick nearly died of severe TB and typhus. He was treated with streptomycin, a recently discovered antibiotic. As a result, he delayed his medical training until 1951.

After making a full recovery, Dick finished his studies and became an anaesthetist at Westminster Hospital. Despite nearly dying in his 20s, he had a successful career working at different hospitals and lived to an old age.

A Medical Student’s Journal – Michael John Hargrave

Michael John Hargrave was another one of the Westminster students that responded to the plea for volunteers. Sadly he passed away at only 50 years old. However, he wrote a diary for his mother, which documents his experience.

After arriving in Germany, he says, “We were told that we were going to start work tomorrow, so far all we had learnt was that we were each going to be given charge of a hut containing 300-500 people.”

On Thursday May 3rd, he writes, “Our job was to see that the food was fairly distributed inside the huts and to give any medical attention we could to inmates.” He later describes looking at some the inmates, “… they were quite literally just a mass of skin and bones, with sunken eyes which had a completely vacant look. They all had terrible bites and severe scabies and some had terrible ulcers and bedsores the size of small saucers, with no dressings on them at all.”

Dealing with disease

Throughout his diary, he describes treating different patients and the diseases they were fighting. He also explains how the group of medical students often became unwell due to the conditions and food too.

His diary highlights the students’ quick thinking and resourcefulness. In one entry he says, “There was one Italian girl… who would certainly die if something was not done quickly. Tried to pass some of the tubing which we had to use as stomach tubes via the nasal route – could not get it down as it kinked… so I passed it orally and much to my surprise it slipped down quite easily (the only lubricant we had was tea!)”.

John Richard ‘Dick’ Everett Jenkins is also mentioned by Hargrave’s, “After lunch I gave Dick Jenkins a hand again, it was extremely hot and there was an overpowering smell of sweltering bodies and faeces; did some dressings and treated more diarrhoea…”

Gruelling work pays off

On May 24th, after the war ended he reports, “We have not got enough time to examine each patient fully and yet there is too much time to do just symptomatic treatment – one thing us certain however, and that is that all patients are looking much better and are stronger though they are still phenomenally thin.”

Imperial College London

9,694 total views