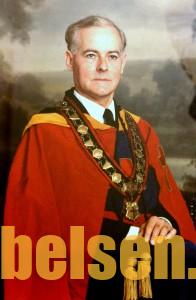

James Henry Molyneaux (Lord)

“If I hadn’t seen what I did at Belsen I don’t think I would have believed someone could do those things to another living person.” Lord Molyneaux

James Henry Molyneaux was born on August 27, 1920 at Killead, Co Antrim, the only son of William Molyneaux, a poultry farmer, and his wife Sarah (née Gilmore). He was educated at Aldergrove School where remarkably he was the only Protestant pupil.

When Sir Knox Cunningham stood down as MP for South Antrim in 1970, Molyneaux was prevailed upon to succeed him. In the General Election he secured a majority just shy of 40,000. In 1974, he became leader of the Unionist MPs at Westminster and in 1979 succeeded Harry West as party leader.

His leadership of the Ulster Unionist Party, from 1979 until 1995, spanned some of the worst violence and political turmoil of the Troubles.

In 1983 he became the MP for the newly-created Lagan Valley seat, which he represented until he stepped down at the General Election of 1997. He was also appointed a Privy Counsellor in 1983, probably the political distinction he valued most. Knighted in 1996, he was awarded a life peerage the following year.

Between 1971 and 1998 James Henry Molyneaux was Sovereign Grand Master of the Royal Black Institution.

He died, aged 94, on March 9, 2015.

Serving in the RAF from 1941 to 1946, Molyneaux became a member of a nine-man specialist group of commandos. They landed on D-Day to reconnoitre for airfield sites on the beachhead, and had Spitfires landing within three days.

In April 1945, his unit assisted in the liberation of Belsen concentration camp, an experience that caused him to suffer nightmares for years. Corporal Jim Molyneaux was 24 years old. What he was to see there was to leave an indelible mark on his life. Fifty-six years later, in 2001, Lord Molyneaux returned to Belsen with a BBC NI Spotlight team to reflect on man’s inhumanity to man. He recalled the horror of the first glimpse of the camp perimeter.

“On that fence were skeletons of men and women, who in sheer desperation had deliberately put their claw-like fingers on that electric fencing and electrocuted themselves and of course no-one bothered to take them off it,” said Lord Molyneaux.

“Every step you took revealed further horrors. It was the sort of stuff of which nightmares were made.”

Seventeen thousand bodies lay scattered and in great heaps inside the camp.

The dead and the living were mingled in the prison huts where indescribable conditions prevailed.

Disease was rife. Typhus had taken hold and would claim 13,000 more lives, even after liberation.

Even the normal human impulse to reach out to the prisoners had to be stifled.

Lord Molyneaux remembered a briefing from the chief medical officer after their arrival.

“He told us: ‘I am warning you not to give them anything to eat, chocolate, sweets, anything because they have deteriorated to such an extent that food of any sort will just kill them stone dead.'”

Cruelty still continued by the German SS guards who had chosen not to flee the camp.

They were still forcing the living to bury their own dead.

“A German soldier was ill-treating two of these prisoners and I have to admit that I broke the Geneva Convention and laid on him with the one stick I could get hold of.”

Above all others one episode stood out for the young soldier Molyneaux.

One morning he came across a Mass being held by some Polish Catholics at a makeshift altar.

“The young priest was standing in a very peculiar attitude and when I came closer to look lying between his feet was the body of another priest who had presumably dropped dead and nobody had the energy to move him.

“It was extremely moving to me as a Protestant and I think I meditated on it for quite a long time afterwards.”

He never forgot his war-time experiences and said that they stood him in good stead for public life.

“You would never write people off as being nonentities.

“I think you would place a certain amount of importance to every human being.”

Some memories were always painful.

“I cannot ever wear striped blue pyjamas for the simple reason that this was the uniform in the concentration camps,” Lord Molyneaux revealed. “If you imagine thousands of people in striped blue and white pyjamas wandering about like skeletons and some of them falling dead before you.

“That’s the memory I think that I would rather not have.”

12,483 total views