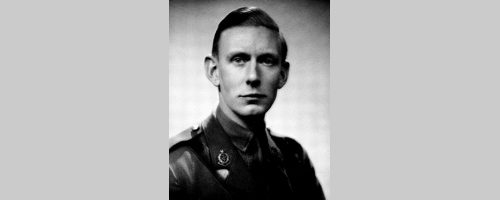

James Kitchener Heath

Adrian Andrews, who lives in Bishop’s Stortford with wife Gunta and their two children, has written a book, A Pithead Polar Bear, about his grandfather’s Second Word War service, including the liberation of Bergen-Belsen concentration camp.

Lance Corporal James Kitchener Heath was born in Staffordshire in 1914 and moved to Burgess Hill, West Sussex, for work. In 1936 he married wife June. Their son, also James, was born in 1939, followed by Adrian’s mother Margaret in 1941.

At the outbreak of war, James travelled to Brighton, where he enlisted with the North Staffordshire Regiment Territorials on January 6, 1940. After basic training, he was sent to Normandy and took part in the Battle of Caen, which raged from June to August 1944.

His regiment was so decimated that he was transferred to the 11th Royal Scots Fusiliers, with whom he fought through France, Belgium and Holland, where he was wounded in the last month of the conflict in Europe.

But none of his experiences on the battlefield could prepare him for the horrors of the Holocaust, as Adrian reveals…

April 15, 2020, marked the 75th anniversary of the liberation of Bergen-Belsen concentration camp by the British Army. Belsen, located in the Lower Saxony region of Germany, was not designated as an extermination camp.

Nevertheless, like Auschwitz and Treblinka, Belsen stands alongside them as an enduring symbol of Nazi depravity.

The camp was put to many purposes during its wartime existence; the incarceration of Russian prisoners of war, Polish ‘Banditen’ from the Warsaw Uprising, along with many other groups deemed to be undesirable in the eyes of the Third Reich – and there were many.

But it was the conditions that prevailed in the camp in the closing months of the European war that sealed its place in infamy.

As the Soviets advanced ever westwards in the direction of Berlin, so the German Army in retreat destroyed the concentration camps in the east and drove prisoners in forced marches towards Germany.

Those that survived these ‘death marches’ and camp transports arrived at Belsen, only to swell the population hugely, above and beyond that which could be managed. As sanitation broke down, typhus raged through the complex.

Liberation revealed the full extent of the humanitarian catastrophe that existed within the camp confines.

Upwards of 10,000 corpses lay unburied among the 55,000 inmates who were themselves, in the majority, sick and starving.

Liberation came too late for many. Thousands and then hundreds died daily as the British tried to bring typhus under control. An estimated 14,000 inmates died in the months from April to July.

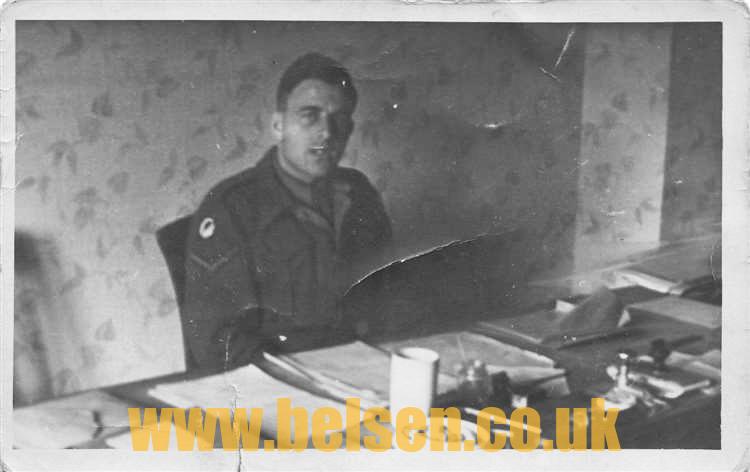

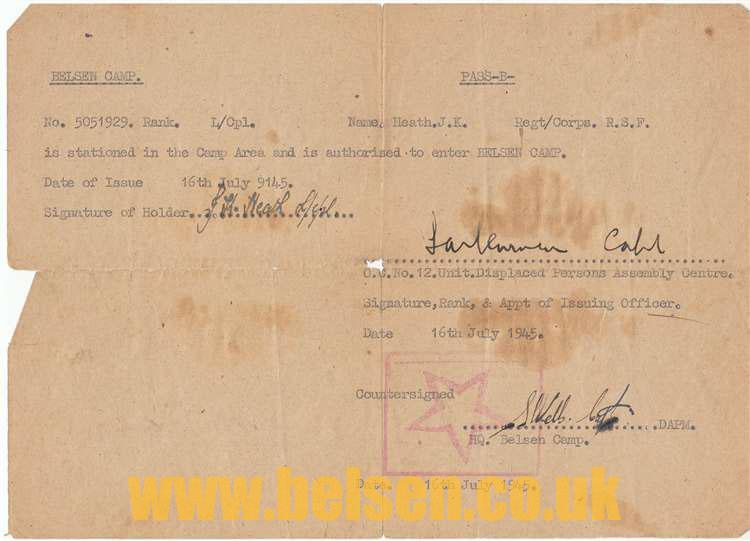

Not all Army personnel who served at the camp were liberators. Many, including my grandfather, L/Cpl James Heath, entered the camp several weeks later in order to oversee the repatriation of ex-prisoners.

A soldier of 11th Battalion, Royal Scots Fusiliers, James was wounded near Nijmegen in Holland on April 7, 1945.

His medical reclassification of A1 to B6 designated him unfit for further fighting but eligible for continued overseas service in a non-combatant role.

Thus he was transferred to a small unit known as 12 DPACS (Displaced Persons Assembly Centre) that had been established in Bruges in Belgium some weeks before.

Prior to entering the camp in mid-July, my grandfather was issued with a double ration of rum, dusted with DDT – an insecticide as protection against contracting the louse-borne typhus – and in he went.

12 DPACS was based in a former Panzer training barracks, known post-liberation as Bergen-Hohne, located two kilometres from the concentration camp area.

Former inmates entered the barracks after passage through the so-called ‘human laundry’, where they were washed, deloused and reclothed in order to prevent the spread of typhus to uninfected areas.

No fewer than 29,000 men, women and children passed through the human laundry as they transited to the barracks and the smaller satellite camps in the vicinity.

Today, as we are in the grip of the Covid-19 pandemic, we look in awe and admiration upon the creation of the Nightingale Hospital, a 2,000-bed facility in the Docklands ExCeL building – well, it has all been done before.

On April 29, 800 Wehrmacht soldiers were removed from the barracks as work started on the preparation of patient wards. Within a month, the Bergen-Hohne barracks had become the largest hospital in Europe, treating 13,000 patients.

At this time, the 12 soldiers who made up the DPACS unit were tasked with facilitating the flow of former prisoners through the barracks hospital and into smaller camps: Russians, Lithuanians, Czechs, Belgians, Hungarians… in fact, citizens of all countries upon which the shadow of occupation fell were grouped together.

These were the first steps towards the repatriation – where the changed political geography of Europe allowed – and reunification of families dispersed over the length and breadth of the concentration camp network that spread across the vast extent of Nazi-occupied Europe.

My grandfather was typically tight-lipped when it came to the months that he spent in Belsen, save to say that the hours were long and the conditions unpleasant.

One thing that he mentioned repeatedly, though, was the stench that pervaded the entire area, even weeks and months after the liberation.

Upon demobilisation, just prior to Christmas 1945, he returned to Sussex with a handful of photographs that show the final destruction of the camp by burning.

Nothing remains of the camp complex now. The site is marked by a number of monuments, some marking the location of mass graves.

A young girl named Anne Frank, along with her sister Margot, who, after enduring the horrors of Auschwitz succumbed to typhus in Belsen just weeks prior to the liberation, is remembered on the site.

As the Holocaust and the camps in which it was perpetrated begins to slip from living memory, we must forever ensure that the message endures – never again.

James Heath died in the Princess Royal Hospital in Haywards Heath, West Sussex, in February 1995. He is interred with June in the cemetery of St Andrew’s Church, Burgess Hill.

10,927 total views