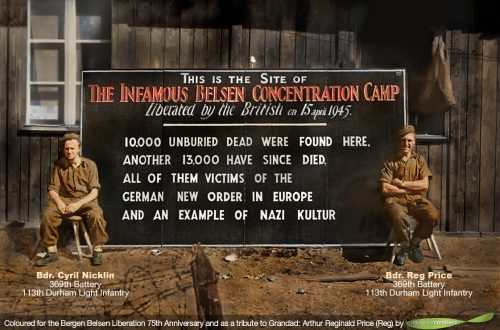

Jim Henderson (113th LAA)

Faded photographs which have been weathered by time still convey the brutal horrors a young soldier witnessed when he helped liberate a Nazi death camp.

Sixty years later, Jim Henderson’s memories of the Bergen-Belsen concentration camp, near Hanover, in Germany, are more vivid than his pile of ragged-edged, blurred snapshots.

“Young people don’t always believe it. It is important to remind them,” said the 83-year-old great grandfather at his home in Huntington, York.

About 60,000 people died at Belsen, which was the first to be freed by British troops on April 15, 1945.

On that day, Jim was on leave, hundreds of miles away, marrying his sweetheart Tess.

His regiment – the 113th Light Anti-Aircraft Regiment, Royal Artillery – had previously taken part in the June 1944 Normandy landings and spent eight weeks at Nijmegen in Holland. The soldiers fought the German counter-attack in the Ardennes, France, on Christmas Day 1944 and later supported the British advance across the River Rhine.

After Jim’s honeymoon, his regiment was ordered to move in and help liberate Belsen.

There were about 40,000 prisoners, no running water and epidemics of typhus, typhoid and tuberculosis.

Many were dying. Thousands had died, their bodies piled high.

Jim remembers skeleton-thin people, wandering aimlessly.

“These people were roaming about; some were naked. They didn’t know what they were doing. They were ravenous. When food came in they tried to get into the cookhouse. Part of our job was to keep them away. All they got was watery soup because they weren’t fit enough to eat anything else.”

Recalling the “walking dead”, he said: “We weren’t allowed to sound a horn. If you came up behind someone who was staggering along, they didn’t know what they were doing. They were just skeletons. If you peeped your horn they were likely to drop dead.”

Survivors in the camp were housed in large huts.

“They were supposed to hold 60 people, but there were 200 to 300 in them just laid where they could find space. They were so far gone that when someone died, they would strip their clothing and use the body for a pillow.

“Doctors sorted out those who would live and those who wouldn’t. They took people fit enough in bus loads to a barracks next door, which was a convalescence hospital, until they were repatriated.”

The soldiers stayed in tented accommodation in a forest opposite Belsen.

Members of Jim’s regiment disinfected people entering and leaving the camp, others guarded its boundary to prevent people breaking out because of the risk of spreading disease.

Some supervised forced labour workers brought in to help.

“They picked up the dead, chucked the bodies into lorries and took them to the graves,” said Jim. “The SS were put down into the graves to level out the bodies which were just tipped in.

“When Belsen was empty it was burned down. We were there right until the end.”

After the war, Jim was a constable with York Police for nine years before moving to London where he served in the Metropolitan Force for 21 years, rising to the rank of chief superintendent, before retiring to York.

York Press, April 30, 2005

7,660 total views