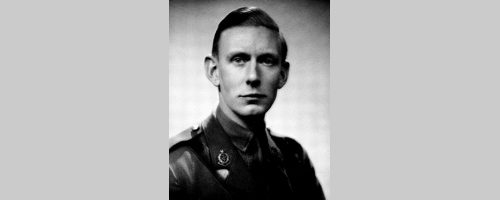

Patrick Mollison CBE (RAMC)

Patrick Mollison was a pioneer in blood transfusion, playing a major role in changing it from a risky procedure to one which is now extremely safe.

The urgent need for blood during World War II provided a stimulus for the development of this important lifesaving measure. His first major contribution was to devise a mechanism whereby blood could be stored for more than just short periods. Mixing donated blood with acid–citrate–dextrose (ACD) became a standard procedure for almost 30 years and was used worldwide.

Patrick Loudon Mollison was born at home in Earl’s Court, London, on 17 March 1914.

Mollison’s research work was then interrupted by military service, when he entered the Royal Army Medical Corps in 1943. He spent time in a field ambulance and as a regimental medical officer in training units in the south of England, and then spent a few months in Germany just as the war was ending. In 1945 he was one of the first doctors to enter the Belsen detention camp as part of the liberation party. This was not a concentration or extermination camp, but a detention camp largely for prisoners of war. The first task on entering the camp was to separate the guards and the prisoners. This proved to be very easy as all the prisoners were emaciated and the guards apparently well fed. They also had to bury many dead prisoners. No one really knew how to safely feed extremely starved patients. The patients themselves were very suspicious of attempts to feed them and would often hide food away under a pillow for later.

He undertook a variety of observational studies on some of the most malnourished prisoners, most of whom were in the camp hospital. Many of the subjects were starving and had been for some time. The malnutrition was compounded by high levels of tuberculosis and typhus. He observed that, even though the prisoners were starving, they were reluctant to eat. His final comment in a report which he wrote to DMS 21 Army Group, was ‘Starving patients are fastidious about their food, and it does not suffice to provide a diet which merely satisfies theoretical nutritional requirements’. He kept meticulous notes and published his findings in the British Medical Journal in 1946. Although this experience must have had a profound effect upon him, he never talked about it either with colleagues or family. In later life he confided to his second wife that he was quite ashamed of the BMJ paper as, in retrospect, it came across as very cold emotionally.

Patrick Mollison CBE

17 March 1914—26 November 2011

9,568 total views